Now in Maharashtra

Now in Maharashtra,EvictionDrive agnaist the Bengali Dalit Refugees, termed As Bangladeshi

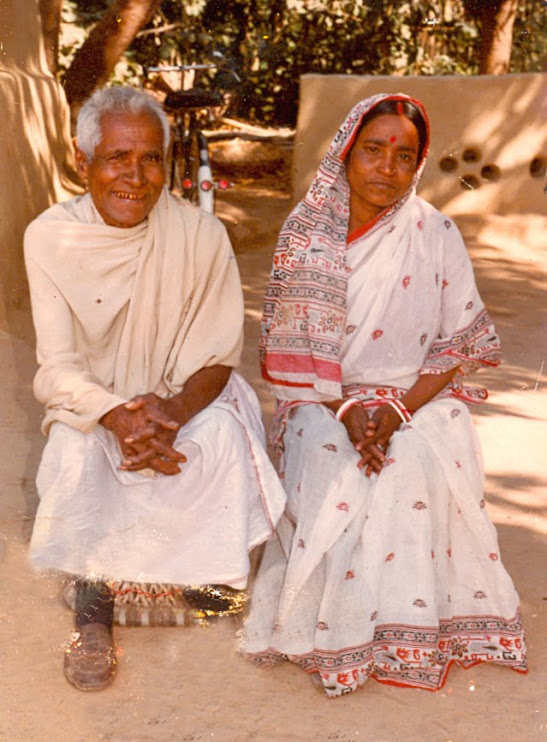

Indian Holocaust My Father`s Life and Time - Eighteen

Palash Biswas

A major misinformation campaign aganaist partition victim Bengali refugees is launched and promoted by castehindu ruling classes in India. We have seen that the then ruling Bjp Government of Uttaranchal denied domicile certifictes to settled bengali Hindu refugees of erly fifties in Uttaranchal in 2001. The nation witnessed the mass movement agnaist this with full local support. In Orrissa, twenty one Bengli partion victim resettlers were deported from Navrangpur district in 2004 and more than fifteen hundred others were served deportation notices in Kendrapara district by Naveen Patnaik government of BJP- BJd combine.Once again the local people protected the refugees. Utkal Bagiya Surakshya Committee led the resistance movement and the administrative action postponed for the time. The next pahase of eviction is to be tried in Malkangiri, wher no less than 215 villages of resettled Bengali refugees exist under Dandkaranya project launched by Mrs Indira Gandhi and the builder of modern Orrissa, Biju Patnaik.

Now it seem to be the turn of Maharashtra where Mulnivasi Bamcef has taken a strong stand and Vaman Meshram raised the issue on international forums. In last September 2005, Mulnivasi Bamcef organised a three day national convention in Maharashtra heart Nagpur aganaist the new citizenship amendment Bill which is used to evict Bengali refugees.

Fiftytwo persons of 15 Bengali Hindu refugee families have been recently arrested from village number sixty one under Arsha Tehseel in Bhandara district. The arrested persons were later released after paying Rs Five thosand Zurmana each and personal bond to submit all documents relating citizenship. Chandrapur and Gadchirauli districts, Naxaliteprone areas of Maharashtra, have the most number of Bengali refugees resettled besides Bhandara. All collectors of Maharashtra Districts have directed the Bengali refugees to submit citizenship documents within a month .

Unlike Punjabi and Tamilrefugees , the Bengali refugees even settled just after partition have not been given Indian citizenship.

Now, it seems Maharashtra ruling classes is prepared to launch a massive Bengali Hindu Dalit refugees eviction drive sooner or later.

The solgan of the misinformation campaign seems to be: Bangla refugees now plague Maharashtra. Mind you Bangla, not Bengali. It denies the hard fact of partition and population transfer thenceforth.It is said, after West Bengal, it is now Maharashtra's turn to acknowledge that the continuing illegal influx of Bangladeshi migrants is a serious problem. The Congress-NCP coalition has asked the Centre to vest officers of the rank of deputy commissioner of police and superintendent of police with powers to arrest and deport illegal Bangladeshi refugees.This was announced, according to an agency report from Mumbai, by deputy chief minister, Chhagan Bhujbal, in the state legislative council.

The decision comes in the wake of evidence of an increasing number of illegal Bangla migrants moving out of their traditional safe havens of Assam, West Bengal and Bihar towards Mumbai and nearby industrial clusters. Mr Bhujbal said the agency report acknowledged that Bangladeshis had settled down at Mira Road in the Thane district. He made a strong case to toughen laws to deal with illegal immigrants, saying the existing ones were a handicap rather than a help for law-enforcement authorities.

The Maharashtra government's new approach comes on the heels of the CPM 's volte-face on the issue of illegal Bangla immigrants.

It is alleged that jettisoning its traditional refusal even to acknowledge the problem, the CPM leadership and West Bengal -CM, Buddhadeb Bhattacharya, have confessed not just its existence but also the crisis-like dimensions it has acquired. Chief minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharya has vested district magistrates with the power to deal with the problem which has altered the demography of the districts sharing borders with Bangladesh, transforming them into Muslim-majority ones.

The chief minister, who was forced to take a hard look at the situation because of the post-9/11 security situation, has even asked for the introduction of identity cards in a clear rebuff to the pro-Left intellectual establishment which routinely discovers Orwellian designs in similar proposals of the Centre.

Mr Bhattacharya, who attracted the wrath of minority representatives and upset his pragmatic colleagues when he asked for surveillance of the madrasas, has also asked for the verification of ration cards in the border districts. As per the new rules, only the district magistrates will have the power to distribute the cards which are illegally procured by the Bangla migrants to flaunt their Indian 'citizenship'.

CCAPT. SIDDHARTH BARVE (barves@bharatpetroleum.com) leads the Mulnivasi Bamcef movement agnaist prosecution of Hindu Bengali Dalit refugees. He wrote:

`This is on the conspiracy hatched by the Manuvadi political parties against our Bengali brethren so that they become aware of the mischief and come together to fight the same.

I went through the Parliament site and collected the Citizenship Amendment Bill. After going through the same and our historical background I have written this article. I then started communicating/writing on the subject to our Bengali writers and editors in Calcutta and I felt ashamed that even most of our Bengali brethren were not aware of the Bill and its contents. But after getting information most of them started publishing articles on this.

You must be aware of a very unfortunate and Black Bill that has been passed by the Indian Parliament in 2003: Citizenship Amendment Bill. In 1955, the Bill was passed by Parliament which stated that all the citizens who migrated to India and who were effected by the partition could be entitled to become citizens of India and their children born on the Indian soil would be natural citizens of this country. The Bill says that the former citizens of India who have surrendered their citizenship and settled abroad shall not be liable for the citizenship of India.

After the partition of East Pakistan, all our Mulnivasi Bengali brethren were residing in Kolna, Jassor, Barisal, Dhaka and Faridpur from where Jogendranath Mandal had got Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar elected to the Constituent Assembly.The Brahmanvadi Congress handed over this part of the country to East Pakistan to punish them for getting Babasaheb elected to the Assembly. Due to the treatment and difficulties many Bengali Mulnivasis came back to India as refugees.

Hate theory: The refugees who had come from Pakistan, particularly the Punjabis and Sindhis who belonged to the upper castes, were given huge amount of money, property, land at low rate and settled to their comfort in big cities and one place. But our brethren were settled in places like Kalahandi and forest and dirty locations where they had to face the miseries and poverty. That is why they were always on the move and did not have any documentary evidence to prove. The Brahmanvadi Congress, BJP and the Hindu nazi parties knew full well that the Bengali refugees were "low castes" but deliberately they spread the lies that the Bangladeshi refugees were Muslims.

So much so even our people (SC/ST of this country) have started hating them thinking them to be outsiders and nothing to do with them. The upper caste Hindus were successful in creating a hate theory against the refugees. We in Maharashtra are not even aware of the plight of our Bengali brethren leave aside fighting for them.

To make the life of our Bengali brethren still worse the then Home Minister Advani, the CM of Assam and the ASU got together in Delhi on March 19, 1999 and hatched a conspiracy declaring the Bengali refugees illegal. It was decided that the children of the Bengali refugees who were born between 1971 and 1986 will be treated as illegal migrants of this country and very harsh and strong action will be taken against them including extraditing them outside India and under no circumstance they will be given citizenship of this country even if they wish to register as citizens of this country.

Congress & CPM support: From this day the conspiracy started in the Home Ministry and they started working on the Amendment of the Citizenship Bill, 1955.

The Amendment Bill was introduced in the Rajya Sabha on May 9, 2003 and it was sent to Pranab Mukherjee for his response so that the same can be passed. On Jan.9, 2004, BJP got the Bill passed with the help and full support of the Congress and the Left parties.

This Bill destroying the future of our Bengali Mulnivasis says that under no circumstance the refugees from Bangladesh can get citizenship of this country and strict legal action will be initiated against them by the government.

With this over two crore Bengali refugees will be affected. The BJP, Congress and the Left parties did not stop there. They wanted to put salt on our wounds and hence in the same Bill they gave dual citizenship (double citizenship) to the upper castes who are staying in 16 different countries so that they never face any problem, and send money to India so that the Hindu nazi parties use them and kill us and vote in the election for the Brahmanwadi BJP or Congress and get elected easily on their votes. This is the biggest conspiracy against our people but not even our educated Bengali SC/ST/BC brothers are aware of this fact — not to speak of our uneducated and poor Bengalis who are going to be thrown out of the country. We are trying to make our people aware of this development so that concrete steps are taken to stop this mass genocide. They have only projected in the media that by this Amendment Bill dual citizenship is granted to people of Indian origin but no where they are saying that the Bill is basically against the Bengali refugees.”

Continued Hindu-Muslim-Sikh Antagonisms.

The termination of British rule in India was greeted enthusiastically by Indians of every religious faith and political persuasion. On Aug. 15, 1947, officially designated Indian Independence Day, celebration ceremonies were held in all parts of the subcontinent and in Indian communities abroad. These ceremonies took place, however, against an ominous background of Hindu-Muslim and Sikh-Muslim antagonisms, which were particularly acute in regions equally or almost equally shared by members of the different faiths.

Population shifts.

In anticipation of border disputes in such regions, notably Bengal and Punjab, a boundary commission with a neutral (British) chairperson was established prior to partition. The recommendations of this commission occasioned little active disagreement with respect to the division of Bengal. In that region, largely because of Gandhi's moderating influence, little communal strife developed. In the Punjab, however, where the line of demarcation brought nearly 2 million Sikhs, traditionally anti-Muslim, under the jurisdiction of Pakistan, the decisions of the boundary commission precipitated bitter fighting. A mass exodus of Muslims from Union territory into Pakistan and of Sikhs and Hindus from Pakistan into Union territory took place. In the course of the initial migrations, which involved more than 4 million persons in the month of September 1947 alone, convoys of refugees were frequently attacked and massacred by fanatical partisans. Coreligionists of the victims resorted to reprisals against minorities in other sections of the Union and Pakistan. Indian and Pakistani authorities brought the strife under control during October, but the shift of populations in the Punjab and other border areas continued until the end of the year. Relations between the two states grew worse in October when the Indian armed forces surrounded Junagadh, a princely state on the Kathiawar Peninsula. This action was taken because the nawab of the state, which had a large majority of Hindus, had previously announced that he would affiliate with Pakistan. The Indian military authorities subsequently assumed control of the state, pending a plebiscite.

Operation Pushback": Sangh Parivar, State, Slums And Surreptitious Bangladeshis In New Delhi

Sujata Ramachandran has written a detailed story in Economic and Political Weekly. She wrote: `The remarkable ease with which the xenophobic tenor of the Hindu Right nationalist organizations or Sangh Parivar found favour with many privileged Indians in the early 1990s cannot be easily or comfortably discounted. Indeed, it even perniciously swayed a moderate secular central government led by the long dominant Congress Party. By mid–1992, when Sangh Parivar made the manifold dangers of the unsanctioned immigration by growing numbers of poverty–stricken Bangladeshi Muslim peasants their rallying cry, the lenient attitude of the Indian state towards these immigrants had hardened with astonishing rapidity. Unsettled by this sweeping tide of Hindu chauvinism, a hurriedly enforced "Action Plan" to locate and identify these undocumented immigrants was followed by brisk efforts under "Operation Pushback" to deport them from New Delhi — India's capital city and locus of bureaucratic, political and financial power. Haphazard and sporadic in implementation, Operation Pushback, while unmasking partisan dispositions coursing through the Indian bureaucracy, also exemplified Congress' belated attempts at redeeming its enervated standing. It is also worth noting that the highly circumscribed material realities of the Bangladeshi immigrants residing in Delhi's numerous slums made them easy targets of these perverse politics, and that subsequent opposition, internally and from neighbouring Bangladesh, to the gratuitous brutality displayed towards the first groups of deportees contributed to the Operation's abrupt truncation.’

In Uttaranchal, an agitation against eviction of Bengali refugees is going on. Some moneylenders turned land mafia have grabbed the land of the poor with the help of police and officials. The lands, which cannot be sold legally, were occupied by the moneylenders. The Kisan Sabha organised demonstrations and the government reluctantly started the negotiation. The demonstrations were conducted on April 16 and 26 against the moneylenders attacking the peasants who participated in demonstrations, when a terror like situation was created. After continuous struggle, some arrests were made and some officials dismissed.

'Operation Pushback'

Sujata Ramchandran Writes,`When the Sangh parivar made unsanctioned immigration by growing numbers of poor Bangladeshi Muslims their new political strategy, the lenient attitude of the ruling Congress government towards the immigrants hardened with astonishing rapidity. Mid-1992 saw brisk efforts made under Operation Pushback to deport them from New Delhi. But the Congress government's easy capitulation to the parivar's rallying cry against unauthorised immigration would become a precursor to its final surrender to the parivar's demolition of the Babri masjid just three months later.

Sujata Ramachandran

I

Introduction

The dramatic shift of Hindu nationalist organisations; the Sangh parivar, from the margins to centre stage of Indian society and politics in the past decade and a half has already been addressed by a fertile and burgeoning literature [Hansen 1999; Jaffrelot 1996; Ludden 1996; Lele 1995; Basu et al 1993]. During this period, the heightened prominence of these saffron forces of Hindu chauvinism in India also drew appreciable attention towards the seemingly unfamiliar, largely unregulated, and surreptitious population flows from neighbouring Bangladesh. That is, their xenophobic discourses characterised these undocumented immigrants, not so much or even commonly as ‘aliens’ or ‘illegal immigrants’, but rather as ‘infiltrators’ representing a visible threat to the long-term existence of an enfeebled Hindu-Indian nation [Ramachandran 1999; Navlakha 1997].1 A substantial body of propaganda texts drafted by the parivar’s ideologues or supporters outside the fold chillingly, solidly, and in great detail outlined the supposed manifold dangers of ‘infiltration’ [Bharatiya Janata Party 1994; Joshi 1994; B Rai 1992, 1993]. The apparition of impoverished, illiterate and bigoted Muslim Bangladeshis migrating en masse as a ‘silent, invisible invasion’ and ‘demographic aggression’ on India began to loom large [Joshi 1994; B Rai 1992, 1993].

An arresting feature of this new development quite clearly was the fervent acceptance, by many respectable Indians, of the anti-Muslim and highly prejudiced discourses zealously promoted by these organisations. But unfortunately, even the Indian state, bureaucracy and other political parties would not remain unaffected for long by its pervasive influence. It would therefore not be an exaggeration to state that in 1992, the situation of undocumented Bangladeshi immigrants living in this country, markedly Muslim ones, began to deteriorate speedily. It is significant to note that many of these undocumented immigrants had been living in several different parts of India for many years as de facto citizens. It was, however, no remarkable coincidence that the central and provincial governments’ overdue recognition of covert population flows into this country materialised exactly at a time when the Sangh parivar made ‘Infiltrators, Quit India’ one of their prominent political and ideological slogans [Ray 1992; Hindustan, October 19, September 29, 1992]. My contention is that it is precisely the saffron surge in India that provided a powerful incentive to the Congress-led government to laggardly attempt to tackle it head-on partly by expelling undocumented Bangladeshis from the capital city [Sonwalkar 1992c].2

Drawing on extensive media coverage and interviews conducted in New Delhi, a textured and hitherto unattempted chronicle of these exclusionary albeit highly rancorous exercises has been provided in this article. The time line of these state-sponsored activities against unauthorised immigrants synchronises with a tumultuous period in recent Indian history, inscribed by large-scale communal riots in various parts of the country [see, for example, Chakravarti et al 1992; Datta et al 1990]. While the adroit collusion by the parivar’s ranks in these exclusionary rituals cannot be overlooked, ‘Operation Pushback’ exemplified a hasty yet haphazard attempt by the long dominant and then ruling Congress at salvaging its own authority in the face of the rising tide of Hindu nationalism. Additionally, ‘Operation Pushback’ was a vulgar manifestation of those partisan tendencies ordinarily camouflaged by the massive Indian bureaucracy. This remarkable narrative also tells us of the more or less willing collaboration between different agencies and departments associated with central and provincial governments in New Delhi and West Bengal. Ultimately, these social evictions signified a less than serious attempt on the part of the Indian state to engage with ‘illegal’ migratory flows from a neighbouring country. A final argument being submitted here is that in addition to political upheaval within this country, activities on the other side of the border – in Bangladesh – substantially influenced the character and duration of these evictions.

Indifference, Impotance, Intolerance

The appearance of undocumented Bangladeshi immigrants in New Delhi’s slums or ‘bastis’ was definitely not a new-sprung occurrence. Evidence gleaned from various sources strongly suggests that small numbers of Bangladeshis lived in several bastis as early as the beginning years of the 1970s [Paul and Lin 1995; The Indian Express, September 23 1992].2 It is also true that for the most part, and for many years, their presence and gradually increasing numbers continued to be tolerated by the Congress backed power-brokers operating through many slums. An early feature on undocumented immigrants in this city corroborates this consequential point [Dutt 1990]. While acknowledging that the Foreigners’ Regional Registration Office (FRRO) had sponsored a study of Bangladeshi settlements in this metropolis as far back as 1988, the mostly disinterested demeanour of the administrative machinery towards these immigrants was recorded:

Apart from occasional raids on their settlements when their shacks are dismantled, official action is rarely initiated against them. It is the FRRO and special branch of the Delhi police that may sometimes decide to do something about the problem. Then, a few people might be taken into custody for a while…But, generally, the police leave them alone (ibid, p 55, emphasis mine).

Anand Prakash, a sub-inspector of the Kotwali police station was quoted in the same report: “We took about 30 people who did not have passports into custody. Twelve men were sentenced to four months’ imprisonment” (ibid, p 57). However, such decisive and draconian action remained fairly uncommon until much later. Also striking is that many of the undocumented immigrants interviewed for this feature in January 1990 were “not bothered about their status as foreigners. Their immediate concern (at that point was) survival” (ibid).

Nevertheless, media reports strongly indicated that in government circles, concern over undocumented Bangladeshis was growing in the late 1980s, even among interest groups well known for supporting these immigrants. One illustration will perhaps be suitable here. More than three years before the first expatriations took place and a formal strategy was instituted, Jyoti Basu, the long-standing chief minister of West Bengal and now retired from the political scene, had sent a letter on irregular migration to then prime minister Rajiv Gandhi (Hindustan, February 27, 1989). Bengal has received substantial numbers of undocumented Bangladeshis in recent years [Samaddar 1999]. In this official communication, he appealed to the central government to focus its attention on the relentless inflow of unauthorised immigrants from across the border. It was alluded that the state government had notified the centre several times of the acutely large numbers of Muslim Bangladeshis entering India through its borders (see also Hindustan, February 28, 1989 and Ghosh Chowdhury 1992).

At first, the Congress government opted to put aside this aggravating issue, partly for the sake of convenience combined with immense constraints posed by the forthcoming general elections. A few months later, its inability to command a majority of Lok Sabha seats in the countrywide elections and the formation after that of a left and centre coalition government that included the Bharatiya Janata Party, further postponed any official-level decision on irregular Bangladeshis [Malik and Singh 1994]. Consequently, when more than a year had expired after Basu’s initial missive to the prime minister, the National Front government publicly proclaimed that it was going to take stern action against undocumented Bangladeshis in West Bengal (Hindustan, May 13, 1990). Notably, the newspaper article exposing this anticipated decision pointed out that the Bharatiya Janata Party had been making an identical demand for a long time. The minister and deputy minister for home affairs were to visit Kolkata for in-depth consultations on various methods to curb ‘illegal’ flows. It is believed that the decision to issue photo-identity documents to Indian residents in border districts was given prominence. Attention was now directed towards stronger border controls to block such migrations [Rakesh 1990].

Ultimately however, it was an Indian government led by the Congress Party under the leadership of Narasimha Rao that after 1991 instated the harshest measures against undocumented immigrants. Highly troubled by uncontrolled violence concomitant with the Sangh-inspired Ramjanmabhumi movement, his regime also suffered from the arduous task of eliminating irregular Bangladeshis. It must be also mentioned that a good year or so would lapse before the Congress-Rao government finally launched their notorious ‘Action Plan’ against Bangladeshis. Documentary evidence apprises us of the government’s willingness finally to own up to the growing presence of Bangladeshi immigrants, yet it continued to waver in its decision to firmly rein in their numbers. As a case in point, consider the statements made by the home minister at the end of 1991. Shankar Rao Chavan had candidly conceded in parliament that the exceedingly generous attitude rife among provincial-level authorities towards undocumented immigrants had mostly contributed to the vast increase in foreign nationals immigrating to India (Hindustan, December 3, 1991). The desperate circumstances in India due to these immigrants, he avowed, had prompted the central government to forthwith grant provincial bureaucracies the legal authority to initiate stern proceedings directed at them (ibid; see also National Herald, September 30, 1992).

Nevertheless, a different source seriously disputed the veracity of the minister’s articulations, making the centre’s lengthened vacillation even more conspicuous. A report published out of Indore in Madhya Pradesh advised that a recently issued order to all Indian provinces to identify foreign citizens living in their areas was proving to be a ‘gigantic crisis’ for this government (Nai Duniya, January 25, 1992). It proceeded to provide us with this rather vital insight:

It is widely believed that following these directives the Uttar Pradesh government had identified 10,000 Bangladeshis in different locations and arrested them for allegedly entering the country without passports. It is also broadly accepted that despite repeatedly inviting input from the central government on how to deal with these ‘uninvited guests’, a prolonged silence from this quarter had forced Uttar Pradesh to eventually release (the detainees) after they had furnished personal bonds (ibid, translation mine).

A final article would lay completely bare the reasons for this extended inactivity in prior years, dubbed scathingly by an editorial as the state’s ‘ostrich-like policy’ (Hindustan Times, October 13, 1992). Curiously, it quoted an unidentifiable though obviously disgruntled individual highly-placed in government circles: ‘No one wanted to rock the boat. (Earlier) there was a lot of buck-passing by government agencies. Besides, there were vested interests – political parties wanted to use them as a vote-bank’ (Indian Express, September 23, 1992; see also September 28, 1992).

I will return to this question of ‘vote-banks’ a bit later on. Suffice it to say, for the longest time, the Indian government and many major Indian political parties remained deeply ambivalent about undocumented Bangladeshi immigrants. But by mid 1992 a turning point had been reached when the heretofore largely ostentatious albeit empty show of official dealings on unsanctioned immigration gave way to brusque displays of coercion. In this detailed elaboration of ‘Operation Pushback’ and the ‘Action Plan’ against Bangladeshis discharged in its premier metropolis, of vital importance is the burgeoning encumbrance of jingoistic sentiments, a difficult burden that had to be encountered intensely on even terms by governments in India and Bangladesh. Bangladesh’s shrill and swift backlash will be examined later, but in India, a moderately secular state that had succumbed sporadically to ethnic and religious tensions in the past, here and now completely shed its thin veneer of neutrality. Narasimha Rao’s rule marked its high point when the state actively embraced a soft sensibility towards the forces of Hindu chauvinism, characterised apropos by Frontline’s editor as a ‘disgraceful and highly risky surrender to the forces of Hindu communalism’ [Ram 1993:9]. The final eye-catching indication for this disturbing trend was that the Indian state now unofficially assigned the unsavory labels of ‘illegal’ immigrant or ‘infiltrator’ almost exclusively to Muslim Bangladeshi immigrants.4

It must be reiterated here that highly alarmed by its considerably weakened political position, the Rao-Congress government suddenly swung into action by launching its ‘Action Plan’ to curb clandestine migration. Although efforts were undertaken in many parts of the country, maximum exertions were actually expended against Bangladeshi immigrants in New Delhi. On initial scrutiny, the decision to concentrate on this city may seem surprising and somewhat unusual. Our astonishment is only compounded when we learn that even the questionable government estimates on undocumented Bangladeshis in this city, between 2,00,000-3,00,000 migrants in most accounts, is miniscule compared to aggregates for other places in north-eastern India closer to the Bangladesh border [Srinivas 1992]. Surely an effective and certainly practical strategy to restrict unauthorised immigrants would have converged, at least in the beginning, on geographical areas in proximity to Bangladesh, namely in provinces like Assam and West Bengal.5

As a sign, however, favouring New Delhi for ‘Operation Pushback’ was much more tactical. This metropolis is the capital city of India and much financial power resides here. More importantly, it is the seat of centralised political power while functioning as the headquarters of the massive Indian administrative machinery that runs the country. At the end though, it was the forthcoming assembly elections for New Delhi held in January 1993 that would dramatically set the stage for the unrestrained aggression towards unauthorised Bangladeshis. Previous election results had already indicated that several prominent Congress leaders, who had exerted considerable influence in the city in the past, were experiencing a noticeable decline in authority. This trend was conspicuous moreover in ‘bastis’ and ‘jhuggi-jhonpris’ (slums and squatters) that had backed these politicians for an extended period by voting en masse for this party, known somewhat sardonically in popular parlance as its ‘vote bank’ [Tiwari 1993; The Indian Express, September 10, 1992].

For our purposes, the term denotes the exploitative system of patronage operating between high-ranking leaders, their agents or powerbrokers within these marginal spaces, and basti or slum residents. Since many slums are unauthorised encroachments on public space or government lands, their permanence plus the occasional additional dispensation of basic benefits to poor urbanites are significantly rooted in these power arrangements. Like other Indian residents, Bangladeshis living in these bastis had also enjoyed the benefits of these meagre disbursements. It had also extraordinarily meant that most Bangladeshis had received the identical treatment as other impoverished Indians. A great majority of them had been issued ration-cards for obtaining subsidised food rations under the government’s public distribution scheme, given identification tokens for their individual jhuggis or squatters, and their names had been recorded in the voting registers (Punjabi 1992). The erosion of Congress power signalled that these informal though weighty arrangements between this party’s politicians and slum residents had been unsettled. And the unhappy outcome was grave for many squatters and especially undocumented Muslim Bangladeshis, who had to forfeit the support that had been previously extended to them by Delhi-level Congress leaders. It is precisely at this precarious juncture that the ‘Action Plan’ and ‘Operation Pushback’ commenced in this city.

II

‘Action Plan’ of Detection, Identification, Deportation

In September 1992, shortly after ‘Operation Pushback’ began, an official spokesperson for the government of India confirmed that the expulsion of several hundred thousand Bangladeshis living ‘illegally’ in border provinces was imminent (Patriot, September 29, 1992b). The state had recently established three steps to deal with unauthorised immigrants: detection, identification, and finally deportation (ibid). Having already detected locations where Bangladeshis existed in large numbers, this spokesperson indicated that the central and state governments were now vigorously involved in identifying Bangladeshis from these Indian areas (ibid).

Accounts quoting home ministry informants reported that the New Delhi administration had set up a special ‘Action Plan’ to identify the undocumented Banglade

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment