Troubled Galaxy Destroyed Dreams- Chapter 534

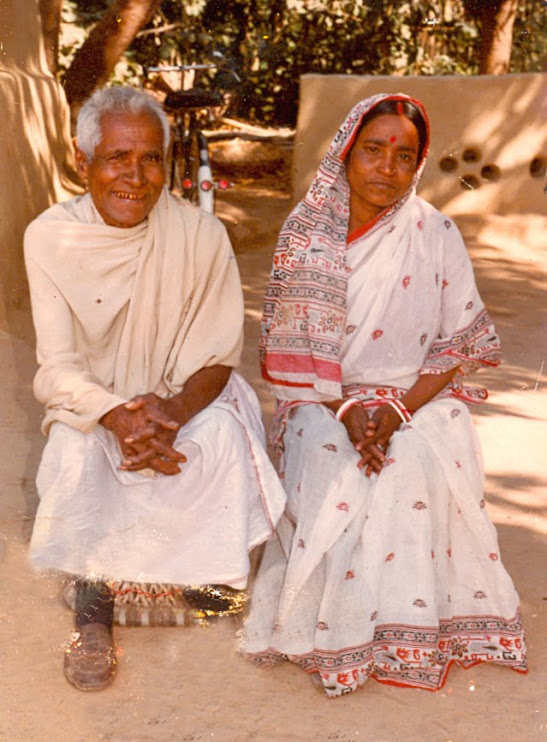

Palash Biswas

http://indianholocaustmyfatherslifeandtime.blogspot.com/

I am pained to visit Rural India to see the systematic Ethnic Cleansing so live! Specially in the land of Scientific Marxist Manusmriti Rule, the perfect case of Exclusive Economy achieved with Surgical Precision in every sphere of life. Now ensured the Exit of the Marxists and Reincarnation of the Kolkata Kali in the Writers, it is High Time to investigate in the Reality of so much so Mythical Land reforms in Bengal. Today the Telegarph has published a story on this. Murshidabad is the only Muslim Dominated district in India which is successful to protect Aboriginal Indigenous Production system and Livelihood despite Victimised by the Free Market Democracy and Political Polarisation. But it has NO Histroy of Communal Turmoil.

| HOW THE LAND WAS WON AND LOST | |

| Sharecroppers in a Murshidabad village are being dispossessed of vested land even as the Left Front crows about land reform, writes Uddalak Mukherjee | |

| The results of the last three electoral contests in West Bengal — the panchayat polls in 2008, the Lok Sabha elections of 2009 and the municipal elections this year — have indicated that the state is in the cusp of a political transition. At a time when the Left Front is ceding considerable ground to its principal opponent, it may be instructive to re-examine the present condition of some of its political programmes that had yielded electoral dividends in the past. One such initiative, undoubtedly, was Operation Barga — the fabled land reform programme, which aimed to redistribute land among sharecroppers (bargadars), legally protect them from forcible eviction by landlords and bestow upon them rights as cultivators. Such a re-examination, despite its localized nature, has the potential to answer two critical questions. First, has the land reform instituted by the Left Front since the late 1970s achieved its intended goal? Second, can the Left Front's continuing dismal performance at the hustings be explained, at least partially, by the persisting problems that have weakened its land reform policy? I travelled to Gangadhari village in Murshidabad recently in search of the answers. Admittedly, it would be unfair to draw conclusions about the pattern, efficacy and problems of land reform in Bengal on the basis of my experiences in a single village in one district. Nonetheless, Gangadhari raises a few uncomfortable questions that must be addressed to understand why the fruits of land reform have eluded the weakest, and hence the most deserving, sections of the peasantry. But why Gangadhari of all places? This village, which is only two kilometres from neighbouring Nadia, has a total land area of 1,424.42 acres, out of which 199.2 acres are vested land. This means that nearly 15 per cent of all land in Gangadhari is 'vested'— plots that were confiscated from landowners (in this case, from the erstwhile zamindar, Balaram Chandra Rudra) and then redistributed among the landless. I was told by the officials concerned that the amount of vested land in Gangadhari is much higher than the approximate state average of five per cent. With such a high incidence of patta distribution, Gangadhari, under the Nowda block, serves as an interesting crucible to test the various claims that are made by this government in the name of land reform. Imagine my surprise when one of the first persons I met in Gangadhari was a landless farmer by the name of Zamiruddin Sheikh. Zamiruddin's fate has been doubly cruel. His father, Chaitan Sheikh, a landless peasant, had received 18 kathas after Operation Barga. However, within a span of a few years, he was forced to 'lease' his land to Abdul Bari Mollah — a Revolutionary Socialist Party leader who, currently, is the chairman of the Nowda panchayat — for Rs 3,000 to meet a medical emergency. Today, Zamiruddin works as a day labourer and makes Rs 1,400 a month, instead of the Rs 2,500 that he requires, he said, to feed the mouths at home. Zamiruddin's plight offers significant insights into the problems that afflict Bengal's land reform programme at present. A sizeable number of farmers, who had received pattas after land redistribution, have now been reduced to landless peasants once again. In Gangadhari alone, I was told that there are over a hundred farmers who have not received pattas or have lost possession of their land. A survey conducted by the West Bengal State Institute of Panchayats and Rural Development some years ago had found that 14.37 per cent of registered sharecroppers have been dispossessed of vested land, over 26 per cent harboured fears of losing their land in the future and 13.23 per cent had lost access to their holdings in the state. But this issue of dispossession is tied to a larger, and more critical, failure. For peasants to prosper, merely transferring the ownership of land is not enough. What is also required, in tandem, is an augmentation of farm productivity and holistic development, something that the Bengal government's land reform policy failed to sustain since that early glimmer of promise. In fact, as early as 1986-88, a survey of the qualitative aspects of land reform in the three districts of Birbhum, Burdwan and Jalpaiguri had noted that even though sharecroppers had received their stipulated plots, farm productivity had been on the wane. According to an independent research report, published in the portal, Science Alert, this June, the contribution of agriculture to West Bengal's State Domestic Product at constant prices has declined from 41.16 per cent in 1970-71 to 27.1 per cent in 2000-01. Significantly, the production of every major crop has dwindled since the 1990s. To take just one example, the output growth rates of aman and boro rice have declined to just 1.04 per cent and 3.35 per cent per annum. There is no reason to believe that the government has been able to reverse the slide since. Gangadhari's shockingly high rates of migration among farming families can be attributed to the lack of employment and the diminishing returns from agriculture. In Gangadhari, reform in the spheres of education and health has been as sporadic. This was, once again, consistent with my earlier experiences of development being dangerously skewed in rural Bengal. During my meeting with the panchayat chairman, he furnished evidence of Gangadhari's 'development'. The village has two primary schools, a primary health centre, two shishu shiksha kendras, a junior high school and a rural library. Given my limited time, I managed to visit the PHC and the school. The health centre, which once provided indoor facilities, was run by a woman, a trained nurse, who usually worked from 10 in the morning. The only doctor, who travelled from Berhampore over 30 kms away, had not turned up on the morning of my visit. The nurse, tired and irritable, informed me that on an average 250 villagers turn up at the PHC to receive treatment for ailments such as fever and malnutrition every single day. Apart from doctors, basic medicines are in short supply. For instance, of the 2,500 paracetamol tablets that were requisitioned by the PHC recently, only 1,000 were sent by the authorities, that too after a month. Next, I visited the Gangadhari H.B. Junior High School. At first, I thought I had been taken to a correctional home by mistake. The school was surrounded by a high wall, and an ancient, enormous lock hung on its gate. The drop-out rate, I was told by a group of young teachers inside, was over 30 per cent and the children, whose parents worked in the nearby brick-kilns, skipped classes regularly. The teachers complained bitterly about the near-absent infrastructure, the inadequate book grant for students, and the government's decision to institute a commission to monitor corporal punishment in district schools. Such a step, they argued, would compromise the standards of discipline among their wards. But let us not forget Zamiruddin and his dead father just yet. Their predicament is a reminder that, in some instances, the philosophy behind Bengal's land reform has been turned on its head as a result of some severe institutional flaws. The law prohibits the selling or leasing of vested land, something that Zamiruddin's father had done to raise money. Biswanath Saha, the land and land reform officer of Nowda block, whom I met later, had initially dismissed the possibility of such malpractices. But, on hearing about Zamiruddin, his confidence seemed to wane. He grudgingly admitted that "only a few instances of irregularities" had come to light during his tenure. Despite his discomfort, Saha took time to explain the process of patta distribution, thereby exposing yet another glaring inconsistency. Under Section 49 (1) of the West Bengal Land Reform Act, said Saha, a joint survey is conducted by the members of the panchayat samiti and the block land and land reform office to identify vested land and their bona fide claimants. On the basis of the findings, a list is prepared and sent to the sub-divisional land and land reform office, which, after completing its own scrutiny, approves the claims. Patta forms are then prepared and pattas distributed in a function, which is often graced by political representatives of the government. Considering the complete politicization of every institution in Bengal, including the bureaucracy, the identification and distribution of pattas in Gangadhari, as in the rest of the state, are blatantly unfair. The RSP is in power in Gangadhari's panchayat. Some of the sharecroppers I met, who are yet to receive pattas even after two decades of land reform, alleged that they have been denied their share because they happen to support the Congress. Before I left the Nowda BLLRO office, Saha gifted me with another, equally startling, piece of information. In Nowda, there have also been instances of vested land — which, according to the law, cannot be purchased, leased or marketed — being sold and the deeds being registered at the district registry office. I could have reminded Saha of his earlier claim that patta distribution has been untouched by corruption. Instead, I thanked him for his time, and the tea, and left. Much of the Left Front's early political gains had been attributed to the success of its land reform programme. But with land reform being severely flawed, at least in its present form, what has been its impact on the coalition's recent political performance in Murshidabad? If the results of the last three assembly elections are looked at, it may seem that a faulty land reform programme has not hurt the Left politically. In the assembly elections of 1996, the Left Front won 10 of the 19 seats; in 2001, its tally rose to 11, and there were significant gains in 2006, given the divided state of the Opposition on that occasion. But democracy is a complicated and tiered political system. A panchayat election, rather than the one that elects a Vidhan Sabha, is a better indicator of the mood and aspirations of a rural people. It is, therefore, telling that at present, in Murshidabad, of the 254 panchayats, the Congress is in power in 157. It is thus difficult to discount the claim that the shortcomings in land redistribution have caused considerable damage to the Left Front in political terms. Gangadhari revealed many bitter truths — dispossessed sharecroppers, uneven social reform that has intensified their penury and hopelessness and institutionalized fallacies that have crippled a programme which, undoubtedly, had the potential to change the future of a people. Unfortunately, the reality in this village also made me realize something else. For all the talk of decentralization of power through panchayati raj — touted as yet another of the Left Front's pioneering initiatives — local leadership at the grassroots continues to be deeply divided on political lines. This saps it of the will to empathize and work for those whom it is meant to serve. I would like to end by recounting two recurring dreams of two different people who live in Gangadhari. The RSP leader and panchayat chairman, now no more young, still dreams of the day during the early stages of Operation Barga. In his dream, he is all of seven, and he sees himself running to plant the red flag on a field that had just been 'liberated' from the zamindar. Zamiruddin, whose father's vested land is now leased to the panchayat chairman, also shared his dream with me. It had nothing to do with his dead father, he said. In it, he only sees the land his family had lost one morning many years ago. | |

| WITH INPUTS FROM ALAMGIR HOSSAIN |

Trains from Murshidabad is Jam Packed and you would Never be able to get an INCH Space to stand anywhere just because the Peasntry is NOT well and People have to go out for Survival. After Grand Success of Land Reforms, as Claimed , it is quite Contradictory.

HOW THE LAND WAS WON AND LOST HOW THE LAND WAS WON AND LOST in Brahamin Marxist Ruled Bengal!

Troubled Galaxy Destroyed Dreams- Chapter 534

Palash Biswas http://indianholocaustmyfatherslifeandtime.blogspot.com/

I am pained to visit Rural India to see the systematic Ethnic Cleansing so live! Specially in the land of Scientific Marxist Manusmriti Rule, the perfect case of Exclusive Economy achieved with Surgical Precision in every sphere of life. Now ensured the Exit of the Marxists and Reincarnation of the Kolkata Kali in the Writers, it is High Time to investigate in the Reality of so much so Mythical Land reforms in Bengal. Today the Telegarph has published a story on this. Murshidabad is the only Muslim Dominated district in India which is successful to protect Aboriginal Indigenous Production system and Livelihood despite Victimised by the Free Market Democracy and Political Polarisation. But it has NO Histroy of Communal Turmoil.

| HOW THE LAND WAS WON AND LOST | |

| Sharecroppers in a Murshidabad village are being dispossessed of vested land even as the Left Front crows about land reform, writes Uddalak Mukherjee | |

| The results of the last three electoral contests in West Bengal — the panchayat polls in 2008, the Lok Sabha elections of 2009 and the municipal elections this year — have indicated that the state is in the cusp of a political transition. At a time when the Left Front is ceding considerable ground to its principal opponent, it may be instructive to re-examine the present condition of some of its political programmes that had yielded electoral dividends in the past. One such initiative, undoubtedly, was Operation Barga — the fabled land reform programme, which aimed to redistribute land among sharecroppers (bargadars), legally protect them from forcible eviction by landlords and bestow upon them rights as cultivators. Such a re-examination, despite its localized nature, has the potential to answer two critical questions. First, has the land reform instituted by the Left Front since the late 1970s achieved its intended goal? Second, can the Left Front's continuing dismal performance at the hustings be explained, at least partially, by the persisting problems that have weakened its land reform policy? I travelled to Gangadhari village in Murshidabad recently in search of the answers. Admittedly, it would be unfair to draw conclusions about the pattern, efficacy and problems of land reform in Bengal on the basis of my experiences in a single village in one district. Nonetheless, Gangadhari raises a few uncomfortable questions that must be addressed to understand why the fruits of land reform have eluded the weakest, and hence the most deserving, sections of the peasantry. But why Gangadhari of all places? This village, which is only two kilometres from neighbouring Nadia, has a total land area of 1,424.42 acres, out of which 199.2 acres are vested land. This means that nearly 15 per cent of all land in Gangadhari is 'vested'— plots that were confiscated from landowners (in this case, from the erstwhile zamindar, Balaram Chandra Rudra) and then redistributed among the landless. I was told by the officials concerned that the amount of vested land in Gangadhari is much higher than the approximate state average of five per cent. With such a high incidence of patta distribution, Gangadhari, under the Nowda block, serves as an interesting crucible to test the various claims that are made by this government in the name of land reform. Imagine my surprise when one of the first persons I met in Gangadhari was a landless farmer by the name of Zamiruddin Sheikh. Zamiruddin's fate has been doubly cruel. His father, Chaitan Sheikh, a landless peasant, had received 18 kathas after Operation Barga. However, within a span of a few years, he was forced to 'lease' his land to Abdul Bari Mollah — a Revolutionary Socialist Party leader who, currently, is the chairman of the Nowda panchayat — for Rs 3,000 to meet a medical emergency. Today, Zamiruddin works as a day labourer and makes Rs 1,400 a month, instead of the Rs 2,500 that he requires, he said, to feed the mouths at home. Zamiruddin's plight offers significant insights into the problems that afflict Bengal's land reform programme at present. A sizeable number of farmers, who had received pattas after land redistribution, have now been reduced to landless peasants once again. In Gangadhari alone, I was told that there are over a hundred farmers who have not received pattas or have lost possession of their land. A survey conducted by the West Bengal State Institute of Panchayats and Rural Development some years ago had found that 14.37 per cent of registered sharecroppers have been dispossessed of vested land, over 26 per cent harboured fears of losing their land in the future and 13.23 per cent had lost access to their holdings in the state. But this issue of dispossession is tied to a larger, and more critical, failure. For peasants to prosper, merely transferring the ownership of land is not enough. What is also required, in tandem, is an augmentation of farm productivity and holistic development, something that the Bengal government's land reform policy failed to sustain since that early glimmer of promise. In fact, as early as 1986-88, a survey of the qualitative aspects of land reform in the three districts of Birbhum, Burdwan and Jalpaiguri had noted that even though sharecroppers had received their stipulated plots, farm productivity had been on the wane. According to an independent research report, published in the portal, Science Alert, this June, the contribution of agriculture to West Bengal's State Domestic Product at constant prices has declined from 41.16 per cent in 1970-71 to 27.1 per cent in 2000-01. Significantly, the production of every major crop has dwindled since the 1990s. To take just one example, the output growth rates of aman and boro rice have declined to just 1.04 per cent and 3.35 per cent per annum. There is no reason to believe that the government has been able to reverse the slide since. Gangadhari's shockingly high rates of migration among farming families can be attributed to the lack of employment and the diminishing returns from agriculture. In Gangadhari, reform in the spheres of education and health has been as sporadic. This was, once again, consistent with my earlier experiences of development being dangerously skewed in rural Bengal. During my meeting with the panchayat chairman, he furnished evidence of Gangadhari's 'development'. The village has two primary schools, a primary health centre, two shishu shiksha kendras, a junior high school and a rural library. Given my limited time, I managed to visit the PHC and the school. The health centre, which once provided indoor facilities, was run by a woman, a trained nurse, who usually worked from 10 in the morning. The only doctor, who travelled from Berhampore over 30 kms away, had not turned up on the morning of my visit. The nurse, tired and irritable, informed me that on an average 250 villagers turn up at the PHC to receive treatment for ailments such as fever and malnutrition every single day. Apart from doctors, basic medicines are in short supply. For instance, of the 2,500 paracetamol tablets that were requisitioned by the PHC recently, only 1,000 were sent by the authorities, that too after a month. Next, I visited the Gangadhari H.B. Junior High School. At first, I thought I had been taken to a correctional home by mistake. The school was surrounded by a high wall, and an ancient, enormous lock hung on its gate. The drop-out rate, I was told by a group of young teachers inside, was over 30 per cent and the children, whose parents worked in the nearby brick-kilns, skipped classes regularly. The teachers complained bitterly about the near-absent infrastructure, the inadequate book grant for students, and the government's decision to institute a commission to monitor corporal punishment in district schools. Such a step, they argued, would compromise the standards of discipline among their wards. But let us not forget Zamiruddin and his dead father just yet. Their predicament is a reminder that, in some instances, the philosophy behind Bengal's land reform has been turned on its head as a result of some severe institutional flaws. The law prohibits the selling or leasing of vested land, something that Zamiruddin's father had done to raise money. Biswanath Saha, the land and land reform officer of Nowda block, whom I met later, had initially dismissed the possibility of such malpractices. But, on hearing about Zamiruddin, his confidence seemed to wane. He grudgingly admitted that "only a few instances of irregularities" had come to light during his tenure. Despite his discomfort, Saha took time to explain the process of patta distribution, thereby exposing yet another glaring inconsistency. Under Section 49 (1) of the West Bengal Land Reform Act, said Saha, a joint survey is conducted by the members of the panchayat samiti and the block land and land reform office to identify vested land and their bona fide claimants. On the basis of the findings, a list is prepared and sent to the sub-divisional land and land reform office, which, after completing its own scrutiny, approves the claims. Patta forms are then prepared and pattas distributed in a function, which is often graced by political representatives of the government. Considering the complete politicization of every institution in Bengal, including the bureaucracy, the identification and distribution of pattas in Gangadhari, as in the rest of the state, are blatantly unfair. The RSP is in power in Gangadhari's panchayat. Some of the sharecroppers I met, who are yet to receive pattas even after two decades of land reform, alleged that they have been denied their share because they happen to support the Congress. Before I left the Nowda BLLRO office, Saha gifted me with another, equally startling, piece of information. In Nowda, there have also been instances of vested land — which, according to the law, cannot be purchased, leased or marketed — being sold and the deeds being registered at the district registry office. I could have reminded Saha of his earlier claim that patta distribution has been untouched by corruption. Instead, I thanked him for his time, and the tea, and left. Much of the Left Front's early political gains had been attributed to the success of its land reform programme. But with land reform being severely flawed, at least in its present form, what has been its impact on the coalition's recent political performance in Murshidabad? If the results of the last three assembly elections are looked at, it may seem that a faulty land reform programme has not hurt the Left politically. In the assembly elections of 1996, the Left Front won 10 of the 19 seats; in 2001, its tally rose to 11, and there were significant gains in 2006, given the divided state of the Opposition on that occasion. But democracy is a complicated and tiered political system. A panchayat election, rather than the one that elects a Vidhan Sabha, is a better indicator of the mood and aspirations of a rural people. It is, therefore, telling that at present, in Murshidabad, of the 254 panchayats, the Congress is in power in 157. It is thus difficult to discount the claim that the shortcomings in land redistribution have caused considerable damage to the Left Front in political terms. Gangadhari revealed many bitter truths — dispossessed sharecroppers, uneven social reform that has intensified their penury and hopelessness and institutionalized fallacies that have crippled a programme which, undoubtedly, had the potential to change the future of a people. Unfortunately, the reality in this village also made me realize something else. For all the talk of decentralization of power through panchayati raj — touted as yet another of the Left Front's pioneering initiatives — local leadership at the grassroots continues to be deeply divided on political lines. This saps it of the will to empathize and work for those whom it is meant to serve. I would like to end by recounting two recurring dreams of two different people who live in Gangadhari. The RSP leader and panchayat chairman, now no more young, still dreams of the day during the early stages of Operation Barga. In his dream, he is all of seven, and he sees himself running to plant the red flag on a field that had just been 'liberated' from the zamindar. Zamiruddin, whose father's vested land is now leased to the panchayat chairman, also shared his dream with me. It had nothing to do with his dead father, he said. In it, he only sees the land his family had lost one morning many years ago. | |

| WITH INPUTS FROM ALAMGIR HOSSAIN |

Trains from Murshidabad is Jam Packed and you would Never be able to get an INCH Space to stand anywhere just because the Peasntry is NOT well and People have to go out for Survival. After Grand Success of Land Reforms, as Claimed , it is quite Contradictory.

HOW THE LAND WAS WON AND LOST HOW THE LAND WAS WON AND LOST in Brahamin Marxist Ruled Bengal!

Troubled Galaxy Destroyed Dreams- Chapter 534

Palash Biswas http://indianholocaustmyfatherslifeandtime.blogspot.com/

I am pained to visit Rural India to see the systematic Ethnic Cleansing so live! Specially in the land of Scientific Marxist Manusmriti Rule, the perfect case of Exclusive Economy achieved with Surgical Precision in every sphere of life. Now ensured the Exit of the Marxists and Reincarnation of the Kolkata Kali in the Writers, it is High Time to investigate in the Reality of so much so Mythical Land reforms in Bengal. Today the Telegarph has published a story on this. Murshidabad is the only Muslim Dominated district in India which is successful to protect Aboriginal Indigenous Production system and Livelihood despite Victimised by the Free Market Democracy and Political Polarisation. But it has NO Histroy of Communal Turmoil.

The Indian Economy Blog » Shallowness of the West Bengal Land Reforms

Land Reforms in West Bengal

Land Reforms in West Bengal. Geography and demography of the state. Situated in the Eastern Coast of India, bordering the states of Bihar and Orissa and the ...

info.worldbank.org/etools/docs/.../West%20Bengal%20PPT.ppt - Similar

THE DIRECTORATE OF LAND RECORDS

Land reform - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

DNA: India - West Bengal withdraws Land Reforms Amendment Bill

www.dnaindia.com/.../report_west-bengal-withdraws-land-reforms-

Land Reform And Farm Productivity In West Bengal

Downloadable! We revisit the classical question of productivity implications of sharecropping tenancy, in the context of tenancy reforms (Operation Barga) ...

ideas.repec.org/p/bos/iedwpr/dp-163.html - Cached - Similar

Land reforms - Kerala versus India | PRAGOTI

Land Reforms

The Telegraph - Calcutta (Kolkata) | Bengal | Maoist 'land reforms ...

www.telegraphindia.com/1100526/jsp/bengal/story_12488503.jsp - Cached

The Hindu : Opinion / News Analysis : Land reform continues in ...

www.hindu.com/2008/08/22/stories/2008082255051100.htm - Cached

| HOW THE LAND WAS WON AND LOST | |

| Sharecroppers in a Murshidabad village are being dispossessed of vested land even as the Left Front crows about land reform, writes Uddalak Mukherjee | |

| The results of the last three electoral contests in West Bengal — the panchayat polls in 2008, the Lok Sabha elections of 2009 and the municipal elections this year — have indicated that the state is in the cusp of a political transition. At a time when the Left Front is ceding considerable ground to its principal opponent, it may be instructive to re-examine the present condition of some of its political programmes that had yielded electoral dividends in the past. One such initiative, undoubtedly, was Operation Barga — the fabled land reform programme, which aimed to redistribute land among sharecroppers (bargadars), legally protect them from forcible eviction by landlords and bestow upon them rights as cultivators. Such a re-examination, despite its localized nature, has the potential to answer two critical questions. First, has the land reform instituted by the Left Front since the late 1970s achieved its intended goal? Second, can the Left Front's continuing dismal performance at the hustings be explained, at least partially, by the persisting problems that have weakened its land reform policy? I travelled to Gangadhari village in Murshidabad recently in search of the answers. Admittedly, it would be unfair to draw conclusions about the pattern, efficacy and problems of land reform in Bengal on the basis of my experiences in a single village in one district. Nonetheless, Gangadhari raises a few uncomfortable questions that must be addressed to understand why the fruits of land reform have eluded the weakest, and hence the most deserving, sections of the peasantry. But why Gangadhari of all places? This village, which is only two kilometres from neighbouring Nadia, has a total land area of 1,424.42 acres, out of which 199.2 acres are vested land. This means that nearly 15 per cent of all land in Gangadhari is 'vested'— plots that were confiscated from landowners (in this case, from the erstwhile zamindar, Balaram Chandra Rudra) and then redistributed among the landless. I was told by the officials concerned that the amount of vested land in Gangadhari is much higher than the approximate state average of five per cent. With such a high incidence of patta distribution, Gangadhari, under the Nowda block, serves as an interesting crucible to test the various claims that are made by this government in the name of land reform. Imagine my surprise when one of the first persons I met in Gangadhari was a landless farmer by the name of Zamiruddin Sheikh. Zamiruddin's fate has been doubly cruel. His father, Chaitan Sheikh, a landless peasant, had received 18 kathas after Operation Barga. However, within a span of a few years, he was forced to 'lease' his land to Abdul Bari Mollah — a Revolutionary Socialist Party leader who, currently, is the chairman of the Nowda panchayat — for Rs 3,000 to meet a medical emergency. Today, Zamiruddin works as a day labourer and makes Rs 1,400 a month, instead of the Rs 2,500 that he requires, he said, to feed the mouths at home. Zamiruddin's plight offers significant insights into the problems that afflict Bengal's land reform programme at present. A sizeable number of farmers, who had received pattas after land redistribution, have now been reduced to landless peasants once again. In Gangadhari alone, I was told that there are over a hundred farmers who have not received pattas or have lost possession of their land. A survey conducted by the West Bengal State Institute of Panchayats and Rural Development some years ago had found that 14.37 per cent of registered sharecroppers have been dispossessed of vested land, over 26 per cent harboured fears of losing their land in the future and 13.23 per cent had lost access to their holdings in the state. But this issue of dispossession is tied to a larger, and more critical, failure. For peasants to prosper, merely transferring the ownership of land is not enough. What is also required, in tandem, is an augmentation of farm productivity and holistic development, something that the Bengal government's land reform policy failed to sustain since that early glimmer of promise. In fact, as early as 1986-88, a survey of the qualitative aspects of land reform in the three districts of Birbhum, Burdwan and Jalpaiguri had noted that even though sharecroppers had received their stipulated plots, farm productivity had been on the wane. According to an independent research report, published in the portal, Science Alert, this June, the contribution of agriculture to West Bengal's State Domestic Product at constant prices has declined from 41.16 per cent in 1970-71 to 27.1 per cent in 2000-01. Significantly, the production of every major crop has dwindled since the 1990s. To take just one example, the output growth rates of aman and boro rice have declined to just 1.04 per cent and 3.35 per cent per annum. There is no reason to believe that the government has been able to reverse the slide since. Gangadhari's shockingly high rates of migration among farming families can be attributed to the lack of employment and the diminishing returns from agriculture. In Gangadhari, reform in the spheres of education and health has been as sporadic. This was, once again, consistent with my earlier experiences of development being dangerously skewed in rural Bengal. During my meeting with the panchayat chairman, he furnished evidence of Gangadhari's 'development'. The village has two primary schools, a primary health centre, two shishu shiksha kendras, a junior high school and a rural library. Given my limited time, I managed to visit the PHC and the school. The health centre, which once provided indoor facilities, was run by a woman, a trained nurse, who usually worked from 10 in the morning. The only doctor, who travelled from Berhampore over 30 kms away, had not turned up on the morning of my visit. The nurse, tired and irritable, informed me that on an average 250 villagers turn up at the PHC to receive treatment for ailments such as fever and malnutrition every single day. Apart from doctors, basic medicines are in short supply. For instance, of the 2,500 paracetamol tablets that were requisitioned by the PHC recently, only 1,000 were sent by the authorities, that too after a month. Next, I visited the Gangadhari H.B. Junior High School. At first, I thought I had been taken to a correctional home by mistake. The school was surrounded by a high wall, and an ancient, enormous lock hung on its gate. The drop-out rate, I was told by a group of young teachers inside, was over 30 per cent and the children, whose parents worked in the nearby brick-kilns, skipped classes regularly. The teachers complained bitterly about the near-absent infrastructure, the inadequate book grant for students, and the government's decision to institute a commission to monitor corporal punishment in district schools. Such a step, they argued, would compromise the standards of discipline among their wards. But let us not forget Zamiruddin and his dead father just yet. Their predicament is a reminder that, in some instances, the philosophy behind Bengal's land reform has been turned on its head as a result of some severe institutional flaws. The law prohibits the selling or leasing of vested land, something that Zamiruddin's father had done to raise money. Biswanath Saha, the land and land reform officer of Nowda block, whom I met later, had initially dismissed the possibility of such malpractices. But, on hearing about Zamiruddin, his confidence seemed to wane. He grudgingly admitted that "only a few instances of irregularities" had come to light during his tenure. Despite his discomfort, Saha took time to explain the process of patta distribution, thereby exposing yet another glaring inconsistency. Under Section 49 (1) of the West Bengal Land Reform Act, said Saha, a joint survey is conducted by the members of the panchayat samiti and the block land and land reform office to identify vested land and their bona fide claimants. On the basis of the findings, a list is prepared and sent to the sub-divisional land and land reform office, which, after completing its own scrutiny, approves the claims. Patta forms are then prepared and pattas distributed in a function, which is often graced by political representatives of the government. Considering the complete politicization of every institution in Bengal, including the bureaucracy, the identification and distribution of pattas in Gangadhari, as in the rest of the state, are blatantly unfair. The RSP is in power in Gangadhari's panchayat. Some of the sharecroppers I met, who are yet to receive pattas even after two decades of land reform, alleged that they have been denied their share because they happen to support the Congress. Before I left the Nowda BLLRO office, Saha gifted me with another, equally startling, piece of information. In Nowda, there have also been instances of vested land — which, according to the law, cannot be purchased, leased or marketed — being sold and the deeds being registered at the district registry office. I could have reminded Saha of his earlier claim that patta distribution has been untouched by corruption. Instead, I thanked him for his time, and the tea, and left. Much of the Left Front's early political gains had been attributed to the success of its land reform programme. But with land reform being severely flawed, at least in its present form, what has been its impact on the coalition's recent political performance in Murshidabad? If the results of the last three assembly elections are looked at, it may seem that a faulty land reform programme has not hurt the Left politically. In the assembly elections of 1996, the Left Front won 10 of the 19 seats; in 2001, its tally rose to 11, and there were significant gains in 2006, given the divided state of the Opposition on that occasion. But democracy is a complicated and tiered political system. A panchayat election, rather than the one that elects a Vidhan Sabha, is a better indicator of the mood and aspirations of a rural people. It is, therefore, telling that at present, in Murshidabad, of the 254 panchayats, the Congress is in power in 157. It is thus difficult to discount the claim that the shortcomings in land redistribution have caused considerable damage to the Left Front in political terms. Gangadhari revealed many bitter truths — dispossessed sharecroppers, uneven social reform that has intensified their penury and hopelessness and institutionalized fallacies that have crippled a programme which, undoubtedly, had the potential to change the future of a people. Unfortunately, the reality in this village also made me realize something else. For all the talk of decentralization of power through panchayati raj — touted as yet another of the Left Front's pioneering initiatives — local leadership at the grassroots continues to be deeply divided on political lines. This saps it of the will to empathize and work for those whom it is meant to serve. I would like to end by recounting two recurring dreams of two different people who live in Gangadhari. The RSP leader and panchayat chairman, now no more young, still dreams of the day during the early stages of Operation Barga. In his dream, he is all of seven, and he sees himself running to plant the red flag on a field that had just been 'liberated' from the zamindar. Zamiruddin, whose father's vested land is now leased to the panchayat chairman, also shared his dream with me. It had nothing to do with his dead father, he said. In it, he only sees the land his family had lost one morning many years ago. | |

| WITH INPUTS FROM ALAMGIR HOSSAIN |

Trains from Murshidabad is Jam Packed and you would Never be able to get an INCH Space to stand anywhere just because the Peasntry is NOT well and People have to go out for Survival. After Grand Success of Land Reforms, as Claimed , it is quite Contradictory.

West Bengal's Jyoti Basu (1914 – 2010) In his long Marxist rule ...

West Bengal's Jyoti Basu (1914 - 2010) in his long Marxist rule, parts of state withered away, literally! While the leading English dailies were praising ...

www.pittsburghpatrika.com/.../west-bengal's-jyoti-basu-1914-2010-in-his-long-marxist-rule-parts-of-state-withered-away-literally/ - CachedWest Bengal - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Communist Party of India (Marxist) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Bengal vs Kerala in the CPM

21 Jul 2010 ... If Bengal's Marxists scored over their Kerala counterparts on Jyoti ... Basu's track record in ruling West Bengal which has gone down in ...

www.thestatesman.net/index.php?option=com_content... - CachedUntouchability in Marxist Bengal - Contribute - MSNIndia

17 Apr 2010 ... Some Marxists conceptualised the Cow belt Theory in absence ofNav Jaagaran ... Hugli of West Bengal under progressive secular Marxist rule! ...

content.msn.co.in/MSNContribute/Story.aspx?PageID=b1ab47a9... - CachedBBC NEWS | South Asia | Marxists accused over Bengal 'terror'

14 Mar 2010 ... Marxists in the Indian state of West Bengal are accused of a campaign ... of federal rule to stop what they call "red terror" in Nandigram. ...

news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/7114827.stm - Cachednandigramunited: Last Marxist Survival Kit of OBC Quota in Bengal ...

15 Jul 2010 ... Untouchability in Marxist Bengal. - by Palash Biswas 17 Apr 2010 ... in District Hugli of West Bengal under progressive secular Marxist rule ...

nandigramunited-banga.blogspot.com/.../last-marxist-survival-kit-of-obc-quota.html - CachedIndiadaily.com - Time for central rule in West Bengal - Communist ...

Time for central rule in West Bengal - Communist Party of India (Marxist) solely responsible for Nandigram bloodbath and massacre : other Left parties in ...

www.indiadaily.com/editorial/18669.asp - CachedBe patient, you can rule Bengal: Advani to Mamata: Rediff.com ...

5 Jun 2010 ... Be patient, you can rule W Bengal, Advani tells Mamata ... UK's colonial dominance, the sun would never set on the Marxist empire," he said. ...

news.rediff.com/report/2010/jun/05/advanis-advice-to-mamata.htm - CachedHimal Southasian/A Marxist and a Gentleman

19 Jan 2010 ... He was a lifelong Marxist and Communist, and was the Chief Minister of Bengal ... For Bengal, the Communist rule from 1977 onward has been a ...

www.himalmag.com/Moving-minarets_fnw15.html - Cached

Welcome to Beach Tree Bengals where my Bengals rule!

kiratisaathi.com - "What do you mean by kirat or Kirati?"

www.kiratisaathi.com/forum.php?P=viewtopic&t=337 - CachedWhat We Learned: Bengals Rule The AFC North - Vinnie Iyer - The ...

Indian Holocaust My Father`s Life and Time: Not Economic, Budget ...

indianholocaustmyfatherslifeandtime.blogspot.com/.../not-economic-budget-nandigramunited: Not Economic, Budget is POLITICAL Meant For ...

nandigramunited-banga.blogspot.com/.../not-economic-budget-is-political-Welcoming The Post Olympics Hockey Hegemony | Cerita Bugil Ngentot

- [ Translate this page ]

ceritacewekngentot.webuda.com/.../Welcoming+the+Post+Olympics+Hockeynandigramunited: Bengal Represented by the Brahaminical Goddess ...

nandigramunited-banga.blogspot.com/.../bengal-represented-by-brahaminicalnandigramunited: Shaffronisation Overlaps Uttarakhand as well as ...

nandigramunited-banga.blogspot.com/.../shaffronisation-overlaps-Manu Rules Zionist Brahaminical India as Jyoti Basu Critical on ...

baesekolkata.ibibo.com/.../322609~Manu-Rules-Zionist-Brahaminical-India-Palash chandra Biswas's Blog at BIGADDA

blogs.bigadda.com/pal4868546/2009/10/page/2/ - SimilarPalash chandra Biswas's Blog at BIGADDA >> RSS,Marxists Backs ...

blogs.bigadda.com/.../rssmarxists-backs-chidambarams-corporate-Quota Politics, Muslims, Jat and MULNIVASI - a knol by Palash Biswas

knol.google.com/k/palash-biswas/quota-politics-muslims-jat.../5 - CachedVictims Of The War Against Terror And Global Zionist Brahaminical ...

hot-trend.info/.../victims-of-the-war-against-terror-and-global-zionist-Genome Research reveals the Euro origin of Aryans, says Palash ...

content.msn.co.in/MSNContribute/Story.aspx?PageID...887b... - Cachedpalashscape: Political ECONOMICS of EXCLUSION! Unilateral ...

palashscape.blogspot.com/.../political-economics-of-exclusion.html - CachedPalash Biswas (palashbiswaskl) on Twitter

twitter.com/palashbiswaskl/ - Cached

Images for Bengal

- Report imagesBengal - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Bengal (cat) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Bengal Products Inc.

News for Bengal

Orissadiary.comSwine flu claims one more life in Bengal - 47 minutes ago PTI Kolkata, Aug 3 (PTI) Swine flu claimed one more life in West Bengal today, taking the number of deaths to four since the outbreak of the viral disease ...IBNLive.com - 38 related articles »Bengal govt gives nod to Mamata's Lalgarh rally - Indian Express - 138 related articles »Delhi held, Bengal sink Mizoram - Hindustan Times - 59 related articles »Bengal cats & kittens - The International Bengal Cat Society ...

The International Bengal Cat Society (TIBCS) is the oldest and largest group of Bengal enthusiasts and breeders in the world. Members are dedicated to the ...

www.tibcs.com/ - CachedCincinnati Bengals

Patrick Kelley's BengalBreed.com: The best Bengal Cat Breeders ...

YouTube - Bathing Bengal

- 1 min - 17 Apr 2006

Bengal cat chasing tail in bathtub. ... 2 weeks ago. lol my bengal would kill me before i can get her into a tub. redkat292 2 weeks ago ...

www.youtube.com/watch?v=jmx3l2NpZ_4 - more videos »Bengal cat guide - Information about bengal cats

Bengal Cats and Bengal Kittens for sale worldwide

Bengali Culture : Bengali Entertainment : Bengali Food

Swine flu claims one more life in BengalIBNLive.com - 48 minutes ago PTI Kolkata, Aug 3 (PTI) Swine flu claimed one more life in West Bengal today, taking the number of deaths to four since the outbreak of the viral disease ... One more dies of swine flu in West Bengal - SifyConstant upsurge of reported cases of swine flu in WB - Health(Y) Destination (blog) H1N1: Dalvi asks officials to remain alert, spread awareness - Times of India Expressindia.com - Release-news.com (press release) all 38 news articles » |  |

Bengal govt gives nod to Mamata's Lalgarh rallyIndian Express - 17 hours ago Ten days after it sought permission from the West Bengal government for holding a rally at Lalgarh, the Trinamool Congress was on Monday granted permission ... Congress welcomes Lalgarh rally under apolitical banner - SifyTrinamool's Lalgarh meeting gets conditional nod - Sify No Trinamool flag at Lalgarh rally - Times of India Calcutta Telegraph - Times of India all 138 news articles » |  |

Delhi held, Bengal sink MizoramHindustan Times - 19 hours ago Later, Shankar Oraon and Gouranga Dutta scored a brace each to help hosts Bengal thrash a hapless 10-man Mizoram After the end of the second round of ... Bengal thrash Mizoram 7-1 in Santosh Trophy - Times of IndiaSantosh Trophy: Bengal crush Mizoram 7-1, Delhi draw 1-1 - Sify Bengal ousts Mizoram in Santosh Trophy - indiablooms Indian Express - Calcutta Telegraph all 59 news articles » |  |

West Bengal government meets non-GJM Hills partiesThe Hindu - 4 hours ago ... which runs the administration in the district, non-GJM Hills parties on Tuesday held parleys with the West Bengal government on the tripartite talks. ... Bengal govt invites Ghisingh for Aug 3 talks - Indian ExpressGJM ignored, Ghising invited for talks - Indian Express Subash Ghising invited to talks on Gorkhaland issue - Daily News & Analysis all 23 news articles » |

Bengal air attack needs healthy Bryantkypost.com - Grant Freking - 1 hour ago GEORGETOWN, Ky - The key to the revitalization of the Bengal passing game isn't rookie wide receiver Jordan Shipley. Or first-round pick Jermaine Gresham. ... All Smiles - Times Tribune of CorbinReport: Gresham to be on the Field by Tuesday - Cincy Jungle (blog) Marvin Lewis confident in managing Owens and Ochocinco - bettor.com (blog) all 305 news articles » |  |

Pro-Maoist group's shutdown paralyses life in West Bengal areasSify - 3 hours ago Normal life was paralysed in Maoist-affected areas of three West Bengal districts Tuesday following a 48-hour shut down call by the pro-Maoist Peoples' ... |

Survey spells poll doom for Left Front in West BengalDaily News & Analysis - Sumanta Ray Chaudhuri - 9 hours ago A grassroots-level survey by the party has projected disaster for the ruling Left Front in West Bengal in the 2011 assembly elections. ... CPI (M) protests illegal inclusion of Photo Identity Cards in West ... - Frontier India - News, Analysis, OpinionTake action against officials adding fake voters: Left - Sify all 8 news articles » |

Bengal to shut Webel CommunicationSify - 2 hours ago West Bengal Information Technology (IT) Minister Debesh Das Tuesday said it might not be possible for the government to run the loss-making Webel ... |

Illegal Bengali immigrant detainedIndependent Online - 10 hours ago Police has confirmed that an illegal immigrant from Bengal who successfully evaded capture for two days has finally been brought to justice. ... |

Bengal IT firms take lead role in Nehru solar missionIndian Express - 13 hours ago West Bengal, along with Gujarat, Rajasthan and Andhra Pradesh, is taking a pioneering role in the Jawaharlal Nehru National Solar Mission (JNNSM) launched ... |  |

Top Stories

Shoot at sight ordered in Kashmir valley; five killedHindustan Times - 1 hour ago A day after Chief Minister Omar Abdullah decided to continue with crackdown on protesters and impose strict curfew in Kashmir to bring some semblance of normalcy, hundreds of protesters defied curfew on Tuesday once again. 5 more killed in violence in Kashmir valley Daily News & Analysis Kalmadi announces inquiry after allegations of forged documentsNDTV.com - 1 hour ago New Delhi: As the allegations of corruption get larger and louder for those involved with the Commonwealth Games, the trouble-shooting for Suresh Kalmadi is becoming tougher. Airlines' financial distress not to affect air safety: PatelTimes of India - 58 minutes ago NEW DELHI: Civil aviation minister Praful Patel on Tuesday said the Director General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) is framing new guidelines to ensure that safety is not affected by the financial distress of airlines. New air safety regulations soon: Praful indiablooms No scare over landing of Cameron's aircraft in Delhi: Praful Patel Daily News & Analysis |

No comments:

Post a Comment